Show them the money: Three-minute macro

Corporate profits are surging, but workers aren’t really sharing in this profit boom—and that’s made even worse by rising prices. Our eyes are also on inventory levels that are building, and which could be a danger in the wake of rising interest rates.

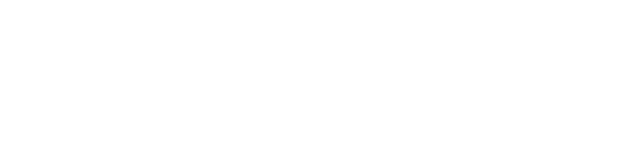

Workers aren’t benefiting from record U.S. corporate profits

In 2021, U.S. corporate profits rose to their highest level ever. One would think that would be great news for the employees of those companies.

One would think.

The reality, however, is that workers haven’t necessarily benefited from the boom in profits. In fact, a closer look at how corporations and workers benefited suggests that the narrative of surging labor power and strong, sticky wage growth may be overblown. Why?

First, real wages (that is, adjusted for inflation) are deeply negative thanks to surging inflation, and in any case, these wage gains (and high turnover levels) are concentrated in sectors that are experiencing acute labor shortages, namely leisure and hospitality.

But not only have nominal wages been flattened by rising prices, but employee compensation as a share of corporate profits has retreated to prepandemic levels. The latest data of employee compensation as a share of our broadest measure of U.S. profits came in at 57.8%—lower than 2019 levels. The significant (albeit fleeting) rise in this ratio during the pandemic signals that corporations have done everything in their power to make sure that profits being passed to their workers aren’t permanent, regardless of the tightness of the labor market. Whether it be signing bonuses, special “one-time” bonuses, or added perks, it’s clear that these measures are transitory in nature.

While the employment picture in the United States remains strong, policy tightening could prove to be a headwind and will be critical to watch as cracks in the unemployment picture could translate into cracks in the U.S. consumer, the largest driver of GDP. Additionally, this data corroborates one of our key ESG themes around the rise of populism and widening inequality.

Workers aren’t benefiting from the boom in corporate profits

U.S. corporate profits and employee compensation

Inventories: different sectors, very different stories

Media and market narratives have certainly reminded us that supply shortages due to a lack of inventories have been a pain point for consumers and as a consequence, the economy. But while overall U.S. inventories don’t look that different from traditional cycles at this stage, and in fact would suggest a further rebuild is required, a closer look at certain sectors reveals that extremes in different industries are causing the aggregate (and headline) figure to balance out, painting a more moderate view.

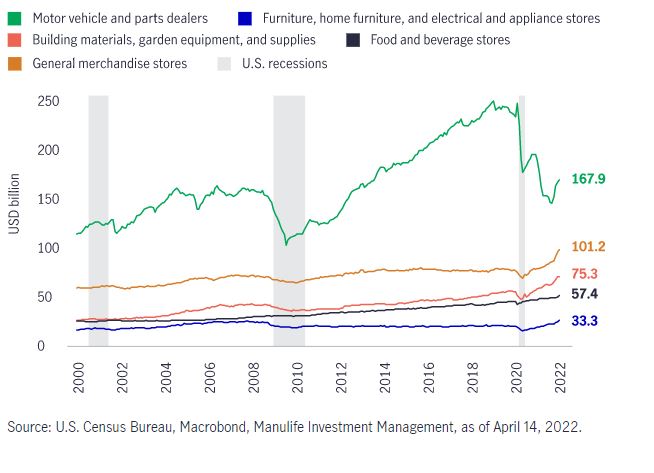

At this stage, the drag on inventories is clearly coming from cars, where inventory levels recently hit their lowest in a decade. This shouldn’t be shocking to anyone in the market for a car as wait times for new cars, surging prices for used cars, and difficulty finding replacement parts for repairs are a nuisance; however, a look at other key sectors shows a completely different picture, with general merchandise stores, building material providers, and furniture and appliance stores all showing alarming buildups recently.

It’s important to note that a common factor linking these sectors is that they’re typically sensitive to interest-rate movements, which have moved aggressively higher these last few months. Consequently, we remain vigilant for signs of cooling demand just as inventories are climbing rapidly higher—this could lead to slowing production and a downside shock to the broader macro picture (though it could provide a reprieve on inflation as well).

Aside from cars, inventories are building

U.S. inventory levels in selected sectors (billions of USD)

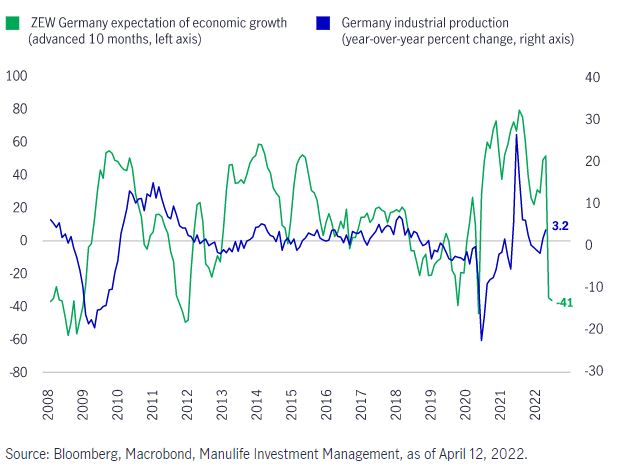

Sentiment in Germany may mean tough times ahead in Europe

Germany’s latest ZEW release (a measure of economic sentiment in the country) has confirmed that the medium-term balance of risk for growth in Europe remains skewed to the downside. The survey is an important barometer for European macro as the expectation’s subcomponent has historically offered critical insight into the outlook for German industrial production with a lead time of about a year. As it stands, this expectation’s subcomponent is at levels last seen in the depths of COVID-19 in 2020 as well as levels that correspond to the European debt crisis and the Global Financial Crisis. As such, we’re expecting low—if not contractionary—levels of growth in Europe in the coming quarters.

Downside risks to European growth are the result of two factors: the energy price shock driven by the war in Ukraine and ongoing growth challenges related to China’s zero COVID-19 policy. We’re doubtful that either of these two factors are likely to shift positively in the near term as Russia appears to be preparing for an extended offensive in Ukraine while China doubles down on restrictions to stem the growth of infections.

German sentiment doesn’t bode well for the industrial powerhouse

Germany ZEW expectations subcomponent vs. industrial production