Cottage or home: which should be a principal residence?

For Canadians with multiple properties and soaring house prices, selling one or more can be a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, you can benefit from strong market conditions; on the other, you have a tough tax decision to make. If you can only have one principal residence exempt from capital gains tax, which house should it be?

Principal residence defined

For tax purposes, a principal residence is a property that you or your spouse1 own and ordinarily inhabit with your minor children, if any, in a year. It can be owned by you or your spouse alone, jointly, or by an eligible trust, and it’s designated as a principal residence. Usually this includes the associated land, up to one-half of a hectare, although more land can be included if you can show it was necessary for the enjoyment of the home. Finally, a principal residence can be any of these housing units:

- a house, cottage, condominium

- an apartment in an apartment building or duplex

- a trailer, mobile home, or houseboat

- a share of the capital stock of a co-operative housing corporation (co-op)

- a leasehold interest in a housing unit.

There are several terms that need clarification:

- ordinarily inhabit – The main reason for owning the property must not be to gain or produce income. Occasional rental income is okay; inhabiting for short periods throughout the year is also acceptable.

- eligible trust – Certain types of trusts can designate a property as a principal residence:

an alter ego trust, joint partner trust, spousal trust, and other lifetime benefit trusts for the settlor’s own exclusive benefit

a qualified disability trust where the electing beneficiary is a resident of Canada; the specified beneficiary of the trust; and a spouse, former spouse, or child of the trust’s settlor

a trust for a specified beneficiary, under 18 years of age and resident in Canada, that arose because of the death of the beneficiary’s mother or father, and the deceased parent is the settlor of the trust.

- designate as a principal residence – This is done on the individual’s or trust’s tax return for the tax year that the property is disposed. Use form T2091 for individuals and T1079 for trusts. It’s also possible to designate a property located outside of Canada as a principal residence if the conditions above are met.

Principal residence exemption

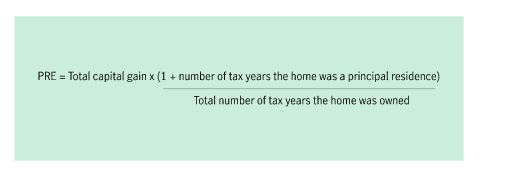

The principal residence exemption (PRE) can exempt up to 100% of the capital gain on a principal residence from tax. To determine the amount of PRE available to offset the capital gain, this formula is used:

The total capital gain is the home’s value at disposition less its adjusted cost base (post-1981 acquisition price and costs + capital improvements). Receipts for improvements during ownership should be kept if the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) requests them. The “1 +” in the numerator is only available to Canadian residents and allows for two principal residences to claim the PRE in the year one is sold and a new one is subsequently purchased. Finally, the denominator is the total number of years the property is owned. This allows for the possibility of a partial PRE, when two or more properties are owned concurrently that could be eligible.

Starting in 1982, only one property could be designated as a principal residence per year per family unit, which includes a spouse or children under 18. For children under 18, this includes parents and unmarried siblings under 18.

If you own more than one property that qualifies as a principal residence and you’re considering selling one or both, which should get the PRE?

Property flipping is when individuals buy and resell homes in a short period of time for a profit. The profits made from flipping real estate are generally considered to be fully taxable as business income. The principal residence exemption doesn’t apply to property flipping.

Case study

Parvin and Preeti are both 60 years old and retiring. They’ve sold their city house and are moving into their cottage. The city house has a substantial profit and they’re wondering if they should use the PRE to shelter the gain from tax or save it for the cottage. Here’s a breakdown of the two properties:

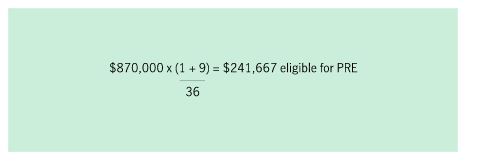

By doing so, we can now compare the total price appreciation for both properties for the time they were owned concurrently. Now, we notice that the city house’s capital gain is $628,333 ($870,000 – $241,667) and the cottage is $625,000. The average gain per year is $23,272 and $23,148 respectively. Applying the PRE to either property generates approximately the same tax savings.

Food for thought

Parvin and Preeti take stock of their overall situation and consider some of their options.

Bird in the hand is worth two in the bush – Consider the future growth of the cottage. Is it expected to increase at a rate that would change its average capital gain? If it’s expected to increase the average, saving the PRE for the cottage may be beneficial; otherwise, using it on the city house now would be preferred.

RRSP contributions – If Parvin and Preeti have unused RRSP contribution room, they could expose enough of the gain on their city house to tax and use an RRSP contribution to defer that tax, saving part of the PRE for the cottage. Since only half of a capital gain is taxable, their total contribution room needs to only be half of the total gain not being covered by the PRE. If they sell the cottage after December 31 of the year they turn 71, they’ll no longer be able to contribute to an RRSP, even if they have unused contribution room.

Charitable donations – If they have philanthropic aspirations, donate an amount that would create a tax credit large enough to offset the gain’s associated taxes.

Life insurance – Life insurance can be used to provide funds to the estate to cover the anticipated tax liability on the cottage for the years that the PRE can’t be used because it was used on the city house. This can be determined by taking half the total unprotected capital gain and multiplying by their marginal tax rate. A joint last-to-die policy will pay out when the second of them dies. This is when the tax liability would come due and the spousal rollover wouldn’t be available.

PRE—a complex but useful tax strategy

The PRE is a valuable, yet complicated tax exemption, especially in the current real estate market. When selling one or more eligible properties that are owned simultaneously, allocating the PRE can be a challenging decision. Start by crunching the numbers to understand where the PRE will provide the greatest tax savings. Then consider your entire financial picture to see if other deductions and credits can reduce taxes. Life insurance can cover any future tax liabilities at death for years the PRE wasn’t available. All of this can help maximize your wealth today and in the future.

1 All references to spouse include common-law partners as defined in the ITA.

![]()