No shortage of risks: Three-minute macro

The Russian-Ukraine conflict, persistently high inflation, and the Fed’s long-awaited rate hike have investors scared, while food prices are increasing at the fastest rate in four decades.

Not all Fed tightening cycles are created equal

As we move further along in the business cycle and closer to central bank tightening, comparisons to previous tightening cycles and how U.S. Treasury rates reacted to them abound. On the surface, it’s easy to compare the tightening cycle we’re entering with those of the past, but we’d caution that not all U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) tightening cycles are created equal. It’s important to differentiate between those that occurred during a weakening macro backdrop from ones taking place during accelerating growth.

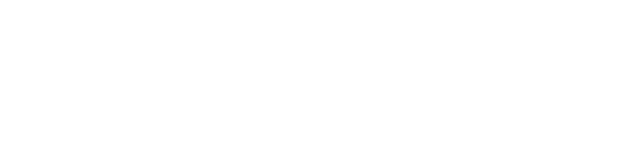

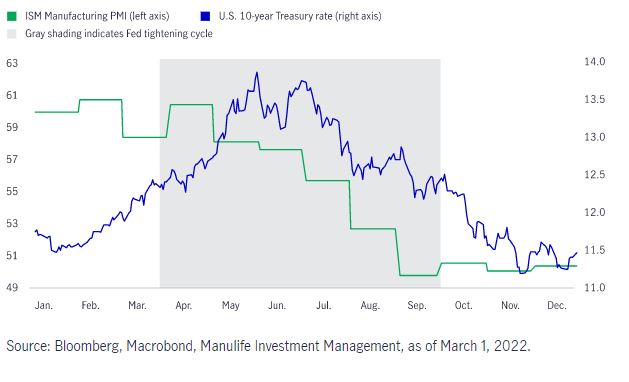

For example, the monetary tightening that the Fed engaged in 1984 and 2004 coincided with periods of moderating GDP growth and declining PMIs. In the former, U.S. Treasury rates increased at the beginning of the cycle but returned back to where they started by the time the Fed ended the tightening. In the 2004 to 2006 period, rates traded rangebound and only increased in the last few months of the approximately two-year-long tightening cycle.

Our base case for 2022 features both decelerating growth (from 5.7% in 2021 to 4.4% in 2022) and lower PMIs. Moreover, the Russia-Ukraine conflict presents heightened geopolitical risk and a higher probability of a stagflationary, downside risk to our base case. In short, it wouldn’t be prudent to assume that Treasury rates will rise just because the Fed is now in tightening mode—history (and economic logic) shows us that the path of the economy has a major impact on market rates, so if the downside risks to our base case do manifest, we might not see the lofty Treasury rate increases that many are expecting.

Treasury rates don’t always rise during tightening cycles

U.S. 10-year Treasury rates and PMIs during 1984 tightening cycle

U.S. 10-year Treasury rates and PMIs during 2004 tightening cycle

Food inflation eats into personal consumption

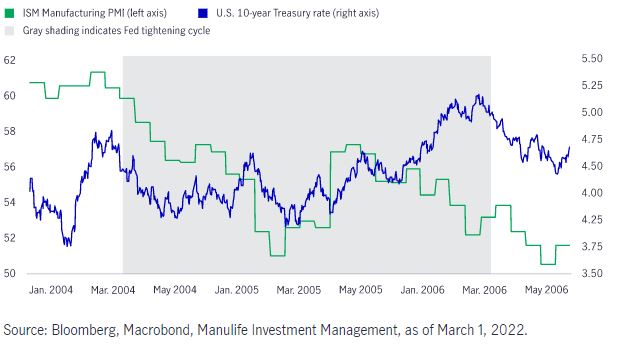

We have long argued that consensus was underpricing a material rise in food inflation, and in the latest CPI data release, food prices rose at a 7.9% pace, the biggest year-over-year increase since 1981. Food price increases therefore continue to eat into personal consumption in the United States. In April 2020, Americans’ spend on food as a percentage of total spending hit 9.4%, the highest value since the early 1990s. But that was largely a function of the denominator in that equation (total food spending) being low, since people weren’t spending much on anything else due to lockdowns. At 7.8% (in January), that figure is below its peak two years ago, but still well above levels over the last 20 years.

Unfortunately, the food categories that have experienced the highest inflation are fruits and vegetables and meat and fish. Given the inelasticity of demand for both food (since people have to eat) and energy (whose prices we know have risen markedly), we see this as a tax to the consumer. The broader implication is ultimately less consumption and therefore a headwind to aggregate demand and growth. And while food inflation in the United States is a drag on the consumer, it’s particularly painful for many emerging-market countries—where food consumption as a percentage of household expenditure is higher—along with countries that rely more heavily on imports for food. Critically, in all countries, painful food inflation widens the income gap and exposes further inequalities, a critical theme as we incorporate environmental, social, and governance issues into our macroeconomic analysis.

Rising food prices are a tax on the consumer

U.S. food price increases and spending since 1980

Risk aversion suggests caution

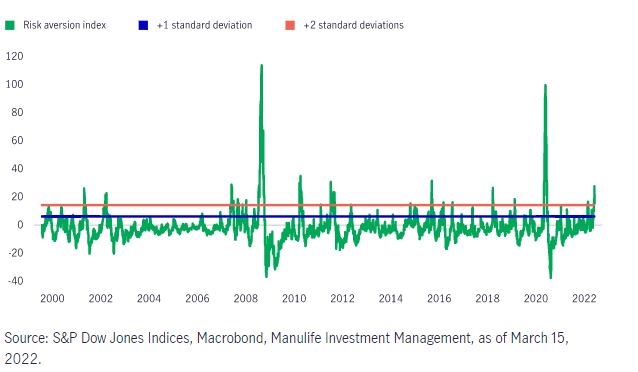

A composite index of risk aversion measuring spread and volatility across credit, equities, emerging markets, and currencies recently reached its highest level since April 2020 (which itself was the highest level since the Global Financial Crisis). Specifically, aggregate market risk aversion is at over two standard deviations above its long-term average. Simply put, the markets are scared.

With few realistic “off-ramps” for deescalation available in the foreseeable future, risk aversion is likely to stay elevated, so we looked at the performance of the S&P 500 Index, the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, the U.S. dollar, and 10-year Treasury yields to get some sense of the risks should risk aversion remain elevated. In general, the results point to weaker equity performance (and emerging-market underperformance), a stronger U.S. dollar, and lower Treasury yields.

At this stage, the demand and supply shocks (reduced global supply of commodities; commodity price inflation; reduced exports to the region; weaker consumer and business sentiment) of the Ukraine crisis are becoming well understood. But we believe an underappreciated macro and market downside risk is that the confluence of risk aversion and sanctions (including “self-sanctioning,” whereby counterparties avoid dealing even in non-sanctioned names to avoid the risk of sanctions come later) could lead to major disruption to global collateral chains and U.S. dollar funding. This development could morph into a funding/liquidity shock, further denting economic growth. Though visible funding stresses are yet to reveal themselves in the current crisis, caution is warranted.

It’s a risk-off world

Market risk aversion index

![]()